7 psychology principles to apply to content design

Simply put, to be a UX professional means to understand how people think and interact with digital experiences. While each of us are different in our own unique way, there are certain truths that define how we tend to behave. The beauty of psychology is its ability to put our everyday behavioural patterns into writing and validate it through experiments, which is pretty much the core of UX.

Susan M. Weinschenk is a psychologist and author of the book 100 things every designer needs to know about people. In it, she presents 100 evergreen principles about how people see, read, think, make decisions, and much more, all of which can help UXers design user-friendly products for people to use.

I also love how each little nugget of fact is presented succinctly under three pages, with studies that provide memorable anecdotes to validate the theory.

I’ve tagged 15 facts that I found super useful for my day-to-day work, and here are the first 7, interjected with my takeaways and thoughts.

People scan screens based on past experience and expectations

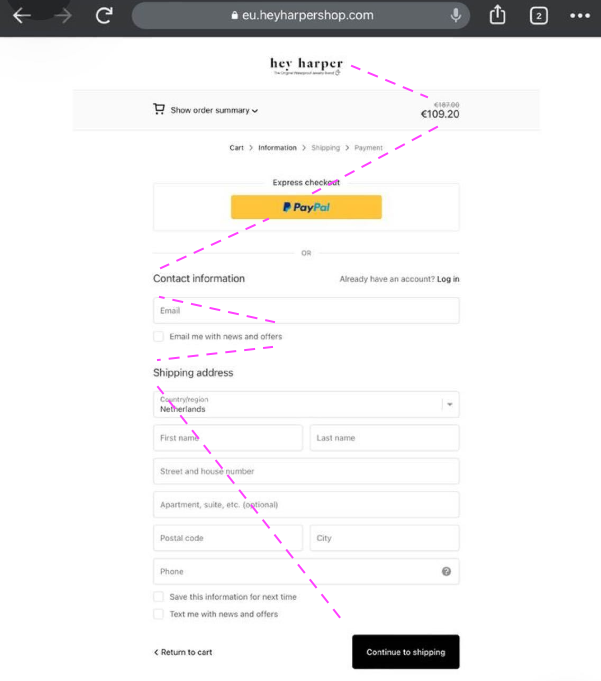

Depending on how someone learned to read and write, and the characteristics of their native language, they expect the screen to be laid out in that order. So for english speakers, their scanning pattern would be from left to right, and top to bottom (also known as the Z-pattern). So if there’s an action to be taken, it should be placed where the user’s reading path ends. Having a CTA button at the bottom right corner of the content’s component would make the most sense.

People also tend to use their central vision to look for meaningful information (about 30% in from the edge and 30% in from the top). So things that are right at the edge of larger screens are likely to get missed.

Also, if an error occurs, people will stop paying attention to the rest of the screen and only focus on the problem area. This means that error messages that tell users how to solve the issue should be contextualised and displayed exactly where the problem occurred.

A simplified example of jewellery brand heyharper.com using the Z-pattern for their checkout page and making sure none of the content goes right to the edge of the desktop screen.

2. People’s ability to read a font affects their perception of the content

While research has shown no difference in comprehension, reading speed or preference between serif and sans serif fonts, overly decorative fonts can affect people’s perception of the content.

A study found that if people are asked to read a task that’s written in a font that’s overly decorative and difficult to read, they will perceive that the task is more difficult to do. While content might be king, the display of the content is just as important in communicating the right message. For digital experiences where we want users to breeze through, like a sign up or checkout process, ornate fonts might give users the impression that the process is a difficult one and cause them to drop off.

3. People read faster with a longer line length, but they prefer a shorter line length

I found this so fascinating as it’s an example of how people might prefer a choice that’s ultimately more ineffective for them.

So a column with a 100-character width is read more quickly than a column with a 45-character width because the former has less interruptions caused by the line breaks. 😮 It makes total sense but somehow I always thought scanning across shorter line lengths allows me to read faster.

The decision that UXers need to make here is, which is more important: speed or conversion? Do you want users to read faster or do you want users to make the decision to read your content? If users are already incentivised to read a piece of content (e.g. breaking news announcement), a longer line length would help them gather information quickly. But if you have promotional content about a new event, you’d want to tap into users’ preference of shorter line lengths to entice them to read the content. Otherwise, they might get turned off by longer line lengths and ignore your content.

4. People reconstruct memories each time they remember them

This principle teaches us that people’s memories can be inaccurate, so it’s important in user research to observe what people do rather than ask them about what they did in the past. If we ask participants to recall about what happened in the past, we must be very intentional about using neutral words and phrases in the interview questions as it may affect the response we get.

In one study, participants watched a video of a car accident and was then asked to estimate the speed of the car when the collision happened. Participants who were asked this with the word “smashed” estimated a higher speed than participants who were asked the same question with the word “hit”.

5. People process information better in bite-sized chunks

As most people can only process 3-4 things at a time, content designers should always think about the best way to design a user flow that applies the concept of progressive disclosure.

By providing the information that people need at that moment in the journey, users are less likely to be overwhelmed and confused. Even if we’re talking about a complex product with a ton of information, users would rather click through multiple pages than be presented with one extremely long page.

If the objective is for users to understand the information on the screen and take the right action at the end of the journey, the number of clicks should not be prioritised as a key metric over churn rate. It’s a better approach to design a longer flow where users have a better chance of reaching the end of the path without dropping out.

6. Some types of mental processing are more challenging than others

Mental processing ranked according to the most difficult to the least difficult:

thinking (cognitive processing)

seeing (visual processing)

doing (motor processing)

This means that it’s easiest for us to tap something on our phones than to look for something on its screen, and even more difficult to remember something we saw on our phones.

The above is a good example of this in action. I was browsing the Apple website for a MacBook, and I found the process of selecting a model so overwhelming with all its many specs that only had slight numerical differences between each model. I might’ve selected something wrongly along the way or have forgotten if I’ve selected something else. So it was really useful to have the full specs available at checkout. Here, I much preferred clicking (motor processing) to see more information on its specs than to try and remember (cognitive processing) what I selected in the previous

7. People interact with conceptual models

A mental model is how people perceive something should work. Besides conducting user research to find out a target audience’s mental model of how the product should work, another in-product solution UXers can propose is to have an onboarding flow or discovery features to help users learn the product’s conceptual model.

If there’s mismatch between a user’s mental model and the product's conceptual model or user experience, the product will be difficult to use.

———

That’s it for now! I’ll follow up about the next 8 facts in the next post.